Life on Earth is amazingly adaptable and includes some animals that survive and thrive even in the harshest conditions. These animals are masters of the extreme, almost shrugging off the notion that life requires a planet in the "Goldilocks Zone", where it's not too hot, not too cold.

Stacker consulted a variety of scientific publications and science communication sites, such as National Geographic and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), to compile a list of 30 animals that live in extreme environments around the world, and searched articles and scientific papers to find ways these animals are adapted to a wide range of challenging conditions.

Some of these animals are found in water so hot it would scald Goldilocks—or you or me. Others frequent deserts where they can drink only rarely, perhaps digging down to find water below the surface, or collecting water from the air. The living may seem easy in freshwater ponds and swamps. Yet if these are in normally arid areas, they will evaporate in the dry season, leaving mud baking beneath the hot sun. For a fish and a toad, the answer involves disappearing beneath the ground, and waiting months (or sometimes years) until the rains return.

To air-breathing spiders, the underwater realm is an extreme environment—yet one resourceful spider evolved to live there by creating its own air chambers. Especially in the Northern Hemisphere, the coming of winter heralds bitter cold that brings snow and ice, along with minimal hours of daylight. For many millions of birds that breed during summer months, this is also time to fly south to the tropics or other, far-flung parts of the Southern Hemisphere. But the world population of one sea duck, spectacled eider, spends winter on open areas between pack ice in the Bering Sea.

The Arctic winter is even more challenging for animals that can’t fly. Caribou migrate only modest distances, and polar bears carry on hunting with dense fur and other adaptations safeguarding them against the cold. While there are animals that hibernate in cozy places, the Siberian salamander is among creatures that can freeze solid and thaw out, ready to breed in the spring.

Though the vast majority of life on Earth depends on photosynthesis powered by sunlight, deep in the oceans there are communities of creatures relying on the heat and chemicals of super-heated emissions from submarine vents. Rocks below ground may also host tiny life forms, like worms that hunt bacteria within damp crevices.

Not all masters of the extreme are so remote from us. Indeed, two are more likely to be found in human homes than in the wild, partly thanks to an ability to quickly evolve resistance to the chemical weapons we spray at them. Keep reading to discover one of the ultimate masters of the extreme which can even survive trips through the vacuum of space.

Stacker consulted a variety of scientific publications and science communication sites, such as National Geographic and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), to compile a list of 30 animals that live in extreme environments around the world, and searched articles and scientific papers to find ways these animals are adapted to a wide range of challenging conditions.

Some of these animals are found in water so hot it would scald Goldilocks—or you or me. Others frequent deserts where they can drink only rarely, perhaps digging down to find water below the surface, or collecting water from the air. The living may seem easy in freshwater ponds and swamps. Yet if these are in normally arid areas, they will evaporate in the dry season, leaving mud baking beneath the hot sun. For a fish and a toad, the answer involves disappearing beneath the ground, and waiting months (or sometimes years) until the rains return.

To air-breathing spiders, the underwater realm is an extreme environment—yet one resourceful spider evolved to live there by creating its own air chambers. Especially in the Northern Hemisphere, the coming of winter heralds bitter cold that brings snow and ice, along with minimal hours of daylight. For many millions of birds that breed during summer months, this is also time to fly south to the tropics or other, far-flung parts of the Southern Hemisphere. But the world population of one sea duck, spectacled eider, spends winter on open areas between pack ice in the Bering Sea.

The Arctic winter is even more challenging for animals that can’t fly. Caribou migrate only modest distances, and polar bears carry on hunting with dense fur and other adaptations safeguarding them against the cold. While there are animals that hibernate in cozy places, the Siberian salamander is among creatures that can freeze solid and thaw out, ready to breed in the spring.

Though the vast majority of life on Earth depends on photosynthesis powered by sunlight, deep in the oceans there are communities of creatures relying on the heat and chemicals of super-heated emissions from submarine vents. Rocks below ground may also host tiny life forms, like worms that hunt bacteria within damp crevices.

Not all masters of the extreme are so remote from us. Indeed, two are more likely to be found in human homes than in the wild, partly thanks to an ability to quickly evolve resistance to the chemical weapons we spray at them. Keep reading to discover one of the ultimate masters of the extreme which can even survive trips through the vacuum of space.

German cockroach and American cockroach

|

| © Ramon(Ray) Evans // GBIF |

While it turns out that cockroaches aren’t especially well-suited to survive radiation following a nuclear holocaust (a myth possibly rooted in the fact that German and American cockroaches are such tough pests), they have several characteristics that enable them to survive and thrive worldwide—especially in the cozy warmth of human homes.

This includes an ability to rapidly evolve resistance to pesticides, by up to six times within just one generation. This stems from cockroaches having a remarkably long genome, which encodes for enzymes needed to combat pesticides, along with an acute sense of smell for detecting food, plus chemical receptors to help them scurry around natural and urban worlds. Undeterred by narrow confines, cockroaches have been found capable of squeezing through horizontal gaps with their bodies compressed by more than 50% and can withstand around 900 times their body weight.

West African lungfish

|

| © South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity // GBIF |

With six species surviving today—four in Africa, one in Australia, the other in South America, lungfish are considered “living fossils” and are the closest living creatures to the ancestors of tetrapods—which include reptiles, amphibians, and mammals.

While they have gills like most fish, lungfish can breathe air using “lungs” that are modified swim bladders. This helps them survive droughts, when then bury into mud, cover themselves in a mucus cocoon, and slow their metabolism in a hibernation-like state called estivation. When there’s enough rain to form a pool again, they emerge—up to six years later.

Himalayan jumping spider

|

| © Jerome // GBIF |

The “omnisuperstes” in this species’ Latin name means "highest of all," reflecting the fact no animals are known to live out their lives as high as Himalayan jumping spiders, climbers have found which at 22,000 feet on Mount Everest.

Like all jumping spiders, they have sharp eyesight thanks to an array of four large eyes on the face, enabling them to spot insects the wind has blown up the slopes, and leap onto their prey.

Ice crawlers

|

| © Sikes // GBIF |

The ice crawler is a curious insect, found in cold places across the northern hemisphere. Its Latin name is based on its appearance, as the spider looks like a combination of crickets (gryll in Greek) and cockroaches (blatta in Greek).

Ice crawlers are omnivorous, and when it’s cold, even below freezing, they scour places like the edges of glaciers and ice caves in search of food such as dead insects. If the temperature rises above 50° F, most species die.

Mountain stone wētā

|

| © Jacob Littlejohn // GBIF |

Wetas are giant flightless crickets unique to New Zealand and include a species that has evolved to cope with the severe cold of the Southern Alps—the mountain stone Weta. When the temperature drops below freezing, the mountain stone weta can freeze too. Later, as the temperature rises again, the weta thaws out, and resumes its life as the largest insect that can tolerate freezing.

Emperor penguin

|

| © Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket // Getty Images |

Standing around 45 inches tall, Emperor penguins are the largest of the world’s penguins and can dive deeper than any other bird—down to 1,850 feet—in search of fish, squid and krill. They have solid bones, rather than the hollow bones typical of birds, to help cope with the extreme water pressures.

Unlike other penguins, Emperor penguins breed during the Antarctic winter. In April, adults leave the sea and march between 30 and 90 miles to places on the ice where they form colonies of up to 10,000 birds. Here, the wind chill can reach -76 degrees Fahrenheit, and when the winds are coldest the penguins form a huddled circle, with any youngsters kept in the warmest center. The huddles slowly rotate, the adults taking turns to take the brunt of the cold on the periphery.

Red flat bark beetle

|

| © Katja Schulz // GBIF |

As its name suggests, the flat bark beetle has a flattened body that enables it to live in gaps below and crevices between the bark of trees such as poplars, ashes, and oaks. Most species are red, probably to warn predators they contain unpalatable and toxic chemicals such as fatty acids, which may also make them resistant to fungi.

Cucujus clavipes—often known as the red flat bark beetle—lives as far north as Canada and Alaska, and the larvae, especially, are specially adapted to sub-zero winter temperatures. Researchers have found that antifreeze proteins plus glycerol help the larvae avoid freezing, and below around -76 degrees Fahrenheit they even vitrify, forming a glassy state. Some larvae cooled to -148 degrees Fahrenheit were still alive after gentle warming.

Arctic lemming

|

| © Сергей Дудов // GBIF |

Arctic lemmings are small rodents found on arctic tundra from north Europe to northeast Russia. They have thick, long fur that helps insulate against the cold. Rather than hibernate, they remain active throughout winter, avoiding the worst of the cold by forming runs and tunnels beneath the snow cover, so they can search for roots and bulbs to eat.

Gray-crowned rosy finch

|

| © mwbirdco // GBIF |

Gray-crowned rosy finches are remarkably hardy birds, breeding on rocky tundra from Alaska south to the heights of mountain ranges including the Sierra Nevada. While many move downslope or migrate south in winter, the rosy finches of the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands are year-round residents.

This toughness is also reflected in the gray-crowned rosy finch probably breeding higher than any other bird in North America, as it nests on the slopes of 20,310-foot Mount Denali.

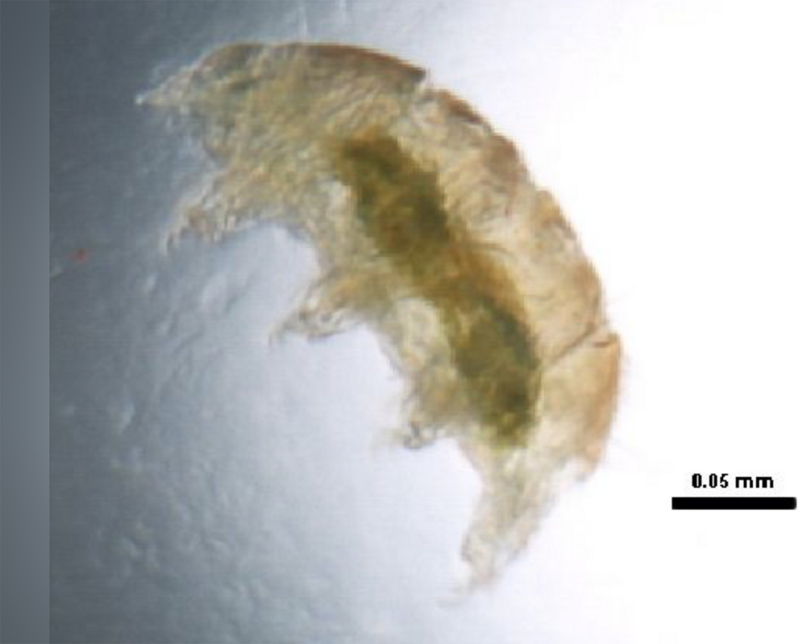

Water bear (tardigrade)

|

| © McInnes // GBIF |

Looking cute-yet-alien in electron microscope photographs, tardigrades—or water bears—are eight-limbed, microscopic multi-segmented animals, mostly less than .04 inches long. Around 1,200 species of tardigrades are known, and they are found all over the planet. Many favor aquatic environments, from coastlines to ocean depths, while others can be found in sediments and arid deserts.

Tardigrades require at least a thin film of water around them to be active, normally living only a few months at most, land-dwelling species have evolved the ability to survive droughts, even forming a dormant, rather shriveled states known as tuns. If wetted three decades or more later, they can come back to life. Tardigrades in the tun state have also survived temperatures as low as liquid helium, -458 degrees Fahrenheit, and as they also resist radiation they have been used in experiments in space, surviving even the space vacuum. But while some have survived temperatures of up to 300 degrees Fahrenheit, tardigrades suffer with long exposure to high temperatures, and this may mean some species will be impacted by climate change.

Caribou

|

| © terence zahner // GBIF |

While caribou are circumpolar, nowadays they are wild or semi-domesticated reindeer in northern Europe and Russia, and the last great wild herds occur in North America, where they are the only deer living year-round north of the treeline.

Caribou are superbly adapted to extreme weather, with hollow hairs providing an insulating coat, and large hooves that both act like snowshoes, and enable them to dig through snow to find the lichen they depend on throughout winter. No other deer have antlers, and while bulls use theirs to defend breeding rights, pregnant females can use theirs in winter to defend feeding areas.

Siberian salamander

|

| © Amaël Borzée // GBIF |

The Siberian salamander has an extensive distribution across north Russia eastwards to Korea and Japan. It’s the only amphibian in the far north of its range, thanks to a superb adaptation to the extreme winter cold—as when temperatures plummet, this salamander can freeze yet remain alive.

When winter approaches, adult salamanders may head to moss near ponds where they can breed in the coming spring. Here, they can freeze without damage by ice crystals, as temperatures drop as low as -22 degrees Fahrenheit. As temperatures rise, the salamanders thaw out and become active; and while the hibernation should only last for one winter, some have been revived after evidently being in permafrost for some years.

Spectacled eider

|

| © Никифорова Валерия // GBIF |

The Spectacled eider is a sea duck that breeds in coastal tundra in Alaska and northeast Russia and feeds mainly on mollusks such as clams and polychaete worms. In winter, the entire world population of around 370,000 individuals congregates in waters around 200 feet deep within the Bering Sea, forming flocks in open patches between sea ice, where their insulation helps withstand the cold.

Polar bear

|

| © Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket // Getty Images |

Unlike their cousins black and brown bears to the south, polar bears do not hibernate. This may be partly due to their specially adapted energy metabolism, allowing them to keep warm with minimum energy loss during times food is hard to find.

Polar bears have various other characteristics that enable them to survive extreme cold, including around four months of winter when the sun barely rises, and monthly temperatures can average -29 degrees Fahrenheit. Their fur is effectively in two layers: dense underfur, and hollow, transparent guard hairs that appear white as they reflect visible light. Below their skin is a layer of fat up to 4.5 inches thick. Massive paws up to 11.8 inches across, with small bumps on their footpads, help give polar bears a firm grip on snow and ice.

Northern viper

|

| © Geir Hermansen // GBIF |

The northern viper is among the most widespread venomous snakes, found across much of Eurasia from the Mediterranean to the Arctic Circle. The viper has such a large range partly as it can hibernate during winter and is remarkably tolerant of cold temperatures. Researchers have found northern vipers can survive being chilled to 23 degrees Fahrenheit and can still move when temperatures fall to 29 degrees Fahrenheit.

Diving bell spider

|

| © Daniele Seglie // GBIF |

While the diving bell spider of northern and central Europe and Asia is one of few spiders to live out their lives underwater, it needs air to breathe—and gathers this in a bubble akin to the diving bells humans once used to explore underwater realms.

To create the “bell”, the spider spins a small underwater web between plant stems. Then it heads to the surface, captures air bubbles with fine hairs on its legs, drops back down to the web and releases the air into the web so it becomes a dome. A few trips later, the spider can fit inside its bubble dome, and ambush prey such as insect larvae, water fleas, and shrimps.

Pompeii worm

|

| © EOL Kanijoman // Flickr |

Named after the Roman city destroyed by a Vesuvius eruption, Pompeii worms are among the most heat-tolerant complex animals known. They are unique to hydrothermal vents deep in the Pacific, forming colonies right beside emissions of acidic water that’s super-heated to 570 degrees Fahrenheit or hotter.

The worms grow in slim tubes up to five inches long, affixed near vents from which they protrude feathery heads into cooler water, probably to feed on microorganisms. The worms exude sugary mucus from glands on their backs, which feeds bacteria forming a thick, fleecy looking “blanket” that helps insulate against the heat.

Common fangtooth

|

| © Sandra Raredon/Smithsonian Institution // Wikimedia Commons |

The common fangtooth is a widely distributed, deep-sea specialist found at depths below most other fish—down to 16,000 feet, where the water is near freezing and the pressure is around 500 times that at sea level. Relative to its size—which is only up to around six inches long, the fangtooth has larger teeth than any other ocean fish. Living in permanent gloom and with poor eyesight, it perhaps uses these teeth to bite whatever it bumps into, hoping this might be a crustacean or another fish of suitable size.

Pacific viperfish

|

| © Alex Bairstow // GBIF |

While Pacific viperfish are among the most fearsome-looking, deep-sea denizens, they grow to only around a foot long. They occur as deep as 14,435 feet, at night swimming up to within several hundred feet of the surface. To attract creatures like shrimp and small fish they feed on, Pacific viperfish are equipped with bioluminescent bacteria in patches known as photophores, which are arrayed along their sides, in their mouths, and on long slim dorsal fins they use as lures.

Frilled shark

|

| © Awashima Marine Park // Getty Images |

Frilled sharks grow more than 6 feet long and are deep ocean predators of depths of around 4,920 feet. As captive Frilled sharks tend to swim with their mouths open, it’s possible they use their bright white teeth to lure the fish and squid they prey on.

Demon worm

|

| © Mirayana M. Barros, Dennis Chang, and Dihong Lu // Wikimedia Commons |

Until 2009, scientists believed that only single-celled life could survive in rocks deep inside the earth. But that year, researchers searching through water from a South African gold mine found tiny demon worms living almost 12,000 feet below the earth’s surface. Here, the worms were feeding on subsurface bacteria living in cracks in the rocks. They are nematode worms, with surface relatives known for tolerating extreme temperatures and dehydration. Demon worms’ ancestors may have descended to the depths long ago.

Giant spider crab

|

| © Takashi Hososhima // Wikimedia Commons |

With a leg span of almost 13 feet, giant spider crabs are the largest arthropods and live at depths of up to 1,300 feet in the Pacific Ocean. Slender bodies encased in tough exoskeletons enable giant spider crabs to readily cope with changes in water pressure as they scurry up and down features on the seabed, preying on smaller creatures and readily scavenging on dead fish and other animals.

Sulfide worm

|

| © Canadian Museum of Nature // GBIF |

As their name suggests, sulfide worms inhabit sulfide chimneys, where sulfur-rich, super-heated water emerges from hydrothermal vents deep in the northwest Pacific. Here, they feed mainly on bacteria. While the surrounding water is freezing, these worms attach and grow in places where the temperature is at least 39 degrees Fahrenheit, up to around 149 degrees Fahrenheit—withstanding the extreme, higher temperatures partly as they contain high amounts of heat-shock proteins. Adding to the challenges, the vent water is oxygen-depleted yet abounds in hydrogen sulfide and would kill most creatures even at normal temperatures.

Giant tube worm

|

| © NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program // Flickr |

Like other denizens of hydrothermal vents, giant tube worms were unknown until researchers venturing to depths of the Pacific at around 5000 feet discovered them living in colonies around the columns of super-heated water. Growing up to eight feet long, these worms are indeed giant and appear striking with their bright red plumes emerging from the tops of whitish chitin tubes. The plumes are red because of hemoglobin, and exchange oxygen, carbon dioxide and other chemicals with the seawater. These nourish symbiotic bacteria that live inside the tube worms, in turn providing the organic molecules that serve as their food.

Vampire squid

|

| © NOAA/MBARI // Flickr |

- Scientific name: Vampyroteuthis infernalis

Reaching just six inches long with blue eyes as big as a dog’s (the largest eyes of any animal relative to its size), vampire squid patrol temperate and tropical oceans at depths of between 300 and 3,000 feet, where almost no light penetrates and oxygen is depleted. Here, they extend thin filaments up to eight times their body length, catching organic detritus such as dead algae, fecal pellets, then hauling these in to gather with their arms, and on to their mouths. The squid’s bodies are arrayed with photophores, and they are skilled at using bioluminescence to produce light shows with these, perhaps to confuse and deter predators.

Reaching just six inches long with blue eyes as big as a dog’s (the largest eyes of any animal relative to its size), vampire squid patrol temperate and tropical oceans at depths of between 300 and 3,000 feet, where almost no light penetrates and oxygen is depleted. Here, they extend thin filaments up to eight times their body length, catching organic detritus such as dead algae, fecal pellets, then hauling these in to gather with their arms, and on to their mouths. The squid’s bodies are arrayed with photophores, and they are skilled at using bioluminescence to produce light shows with these, perhaps to confuse and deter predators.

Arabian camel

|

| © Edwin Remsberg/VWPics/Universal Images Group // Getty Images |

- Scientific name: Camelus dromedarius

Even when the desert heat in northern Africa and southwest Asia reaches 120 degrees Fahrenheit, Arabian camels barely break into a sweat. Their supreme adaptations to desert life also include being able to journey 100 miles without drinking; and when they do reach water, camels are capable of drinking 30 gallons of water in just 13 minutes. Plus, of course, Arabian camels have their famous single humps, in which they store not water but fat—accumulating as much as 90 pounds of fat they can convert to water and energy when the need arises. Dense eyebrows and long eyelashes help keep sand from their eyes, and they are equipped with large footpads that enable them to stride over sand and rocks.

Even when the desert heat in northern Africa and southwest Asia reaches 120 degrees Fahrenheit, Arabian camels barely break into a sweat. Their supreme adaptations to desert life also include being able to journey 100 miles without drinking; and when they do reach water, camels are capable of drinking 30 gallons of water in just 13 minutes. Plus, of course, Arabian camels have their famous single humps, in which they store not water but fat—accumulating as much as 90 pounds of fat they can convert to water and energy when the need arises. Dense eyebrows and long eyelashes help keep sand from their eyes, and they are equipped with large footpads that enable them to stride over sand and rocks.

Water-holding frog

|

| © Auscape/Universal Images Group // Getty Images |

- Scientific name: Litoria platycephala

In times of plenty, southern Australia’s water-holding frogs roam grasslands and temporary swamps while feeding on insects and small fish. But when the weather turns hot and dry, they show a remarkable ability that enables them to survive. Water-holding frogs then burrow into the mud and secrete mucus around their skin. This mucus forms “cocoons”, and the frogs remain ensconced within. There, the frogs’ metabolisms slow as they remain in a hibernation-like state. When rains return, the frogs break through their cocoons, dig to the surface, and resume their lives.

In times of plenty, southern Australia’s water-holding frogs roam grasslands and temporary swamps while feeding on insects and small fish. But when the weather turns hot and dry, they show a remarkable ability that enables them to survive. Water-holding frogs then burrow into the mud and secrete mucus around their skin. This mucus forms “cocoons”, and the frogs remain ensconced within. There, the frogs’ metabolisms slow as they remain in a hibernation-like state. When rains return, the frogs break through their cocoons, dig to the surface, and resume their lives.

Desert elephant

|

| © Hoberman/Universal Images Group // Getty Images |

- Scientific name: Loxodonta africana

While African bush elephants are typically fond of water, drinking daily and enjoying mud baths, desert-adapted populations in Namibia and Mali can survive in dry, hot conditions reaching 122 degrees Fahrenheit. Adult females and the young drink perhaps once in three days, while bulls might last five days without water.

Elephants are renowned for their long memories, and these help those in the desert to return to places with water, where they might use their trunks and legs to dig to reveal water below the surface. At times, desert elephants walk more than 40 miles between water holes and feeding areas. With food scarce, their family units are smaller than those of elephants roaming lush savannahs.

While African bush elephants are typically fond of water, drinking daily and enjoying mud baths, desert-adapted populations in Namibia and Mali can survive in dry, hot conditions reaching 122 degrees Fahrenheit. Adult females and the young drink perhaps once in three days, while bulls might last five days without water.

Elephants are renowned for their long memories, and these help those in the desert to return to places with water, where they might use their trunks and legs to dig to reveal water below the surface. At times, desert elephants walk more than 40 miles between water holes and feeding areas. With food scarce, their family units are smaller than those of elephants roaming lush savannahs.

Couch’s spadefoot toad

|

| © Bryan Box // GBIF |

As summer thunderstorms arrive in the southwestern U.S. and western Mexico, the low-frequency sounds they emit signal to Couch’s spadefoot toads below ground that it’s time to dig to the surface. Once emerged, males find pools and call to attract females, which lay eggs. The eggs are fertilized, and breeding activity may end just 24 hours later. Adults now focus on feeding, eating enough in a night or two to last until the next year. Then, with their hindfeet—each equipped with keratinous “spade”, they burrow back into the ground. Here, they return to hibernation-like estivation, untroubled by the land above become arid once more.

Namib Desert darkling beetles

|

| © hermanviviers // GBIF |

- Scientific name: Stenocara gracilipes

Though there is little rain in the Namib desert, on at least 30 days each year breezes blowing over the cold waters of the nearby ocean bring fog that can reach 62 miles inland, with moisture harvested by specially adapted darkling beetles.

These include the fog-basking beetle, which climbs sand dunes on early mornings, and stands with back raised, head lowered, so water droplets collect on its body and trickle down to its mouth. Scientists have found the beetle’s water-collecting ability depends on microscopic surface features, which might lead to artificial materials to help people harvest water from the air, such as in refugee camps.

Though there is little rain in the Namib desert, on at least 30 days each year breezes blowing over the cold waters of the nearby ocean bring fog that can reach 62 miles inland, with moisture harvested by specially adapted darkling beetles.

These include the fog-basking beetle, which climbs sand dunes on early mornings, and stands with back raised, head lowered, so water droplets collect on its body and trickle down to its mouth. Scientists have found the beetle’s water-collecting ability depends on microscopic surface features, which might lead to artificial materials to help people harvest water from the air, such as in refugee camps.